Use case #01: A day in daylight

Open and reproducible analysis of light exposure and visual experience data (Advanced)

1 Preface

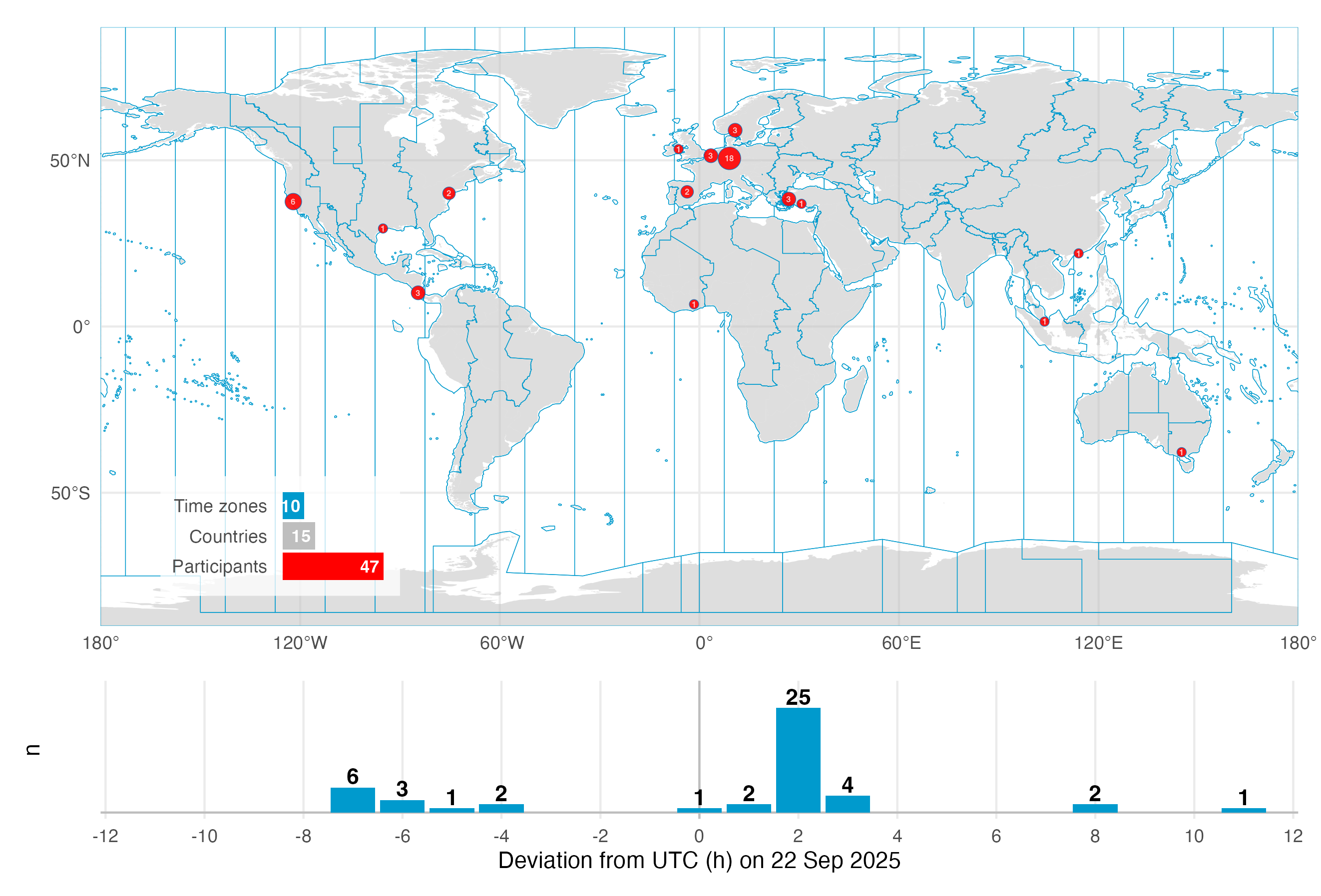

On the September 2025 equinox, over 50 participants across the globe logged and annotated their daily light exposure. While not a (traditional) study, the data is extraordinarily well suited to explore a diverse dataset across many participants in terms of geolocation, device-type, and contextual information, as participants logged their statechanges via a smartphone application. The dataset were analysed and presented as part of the A Day in Daylight event on 3 November 2025. They can be explored in an interactive dashboard. For this use case, we will take a subset of the datasets to explore workflows for these conditions, and summarize the data by combining it with activity logs and participant demographics.

The tutorial focuses on

setting up the import from multiple devices and time zones & handling once the data is imported

handling a large number of participants in a study

adding to and analysing participant-specific data (sex, age,…)

adding to and analysing activity logs from participants

Note that we will use a reduced dataset for the live tutorial of 10 participants for the wearable data.

2 How this page works

This document runs a self‑contained version of R completely in your browser1. No setup or installation is required.

As soon as as webR has finished loading in the background, the Run Code button on code cells will become available. You can change the code and execute it either by clicking Run Code or by hitting CTRL+Enter (Windows) or CMD+Enter (MacOS). Some code lines have commments below. These indicate code-cell line numbers

You can execute the same script in a traditional R environment, but this browser‑based approach has several advantages:

- You can get started in seconds, avoiding configuration differences across machines and getting to the interesting part quickly.

- Unlike a static tutorial, you can modify code to test the effects of different arguments and functions and receive immediate feedback.

- Because everything runs locally in your browser, there are no additional server‑side security risks and minimal network‑related slowdowns.

This approach also comes with a few drawbacks:

- R and all required packages are loaded every time you load the page. If you close the page or navigate elsewhere in the same tab, webR must be re‑initialized and your session state is lost.

- Certain functions do not behave as they would in a traditional runtime. For example, saving plot images directly to your local machine (e.g., with

ggsave()) is not supported. If you need these capabilities, run the static version of the script on your local R installation. In most cases, however, you can interact with the code as you would locally. Known cases where webR does not produce the desired output are marked specifically in this script and static images of outputs are displayed. - After running a command for more than 30 seconds, each code cell will go into a time out. If that happens on your browser, try reducing the complexity of commands or choose the local installation.

- Depending on your browser and system settings, functionality or output may differ. Common differences include default fonts and occasional plot background colors. If you encounter an issue, please describe it in detail—along with your system information (hardware, OS, browser)—in the issues section of the GitHub repository. This helps us to improve your experience moving forward.

3 Recording

You can follow along with the recordings to get even more context about the workflow in LightLogR.

4 Setup

We start by loading the necessary packages.

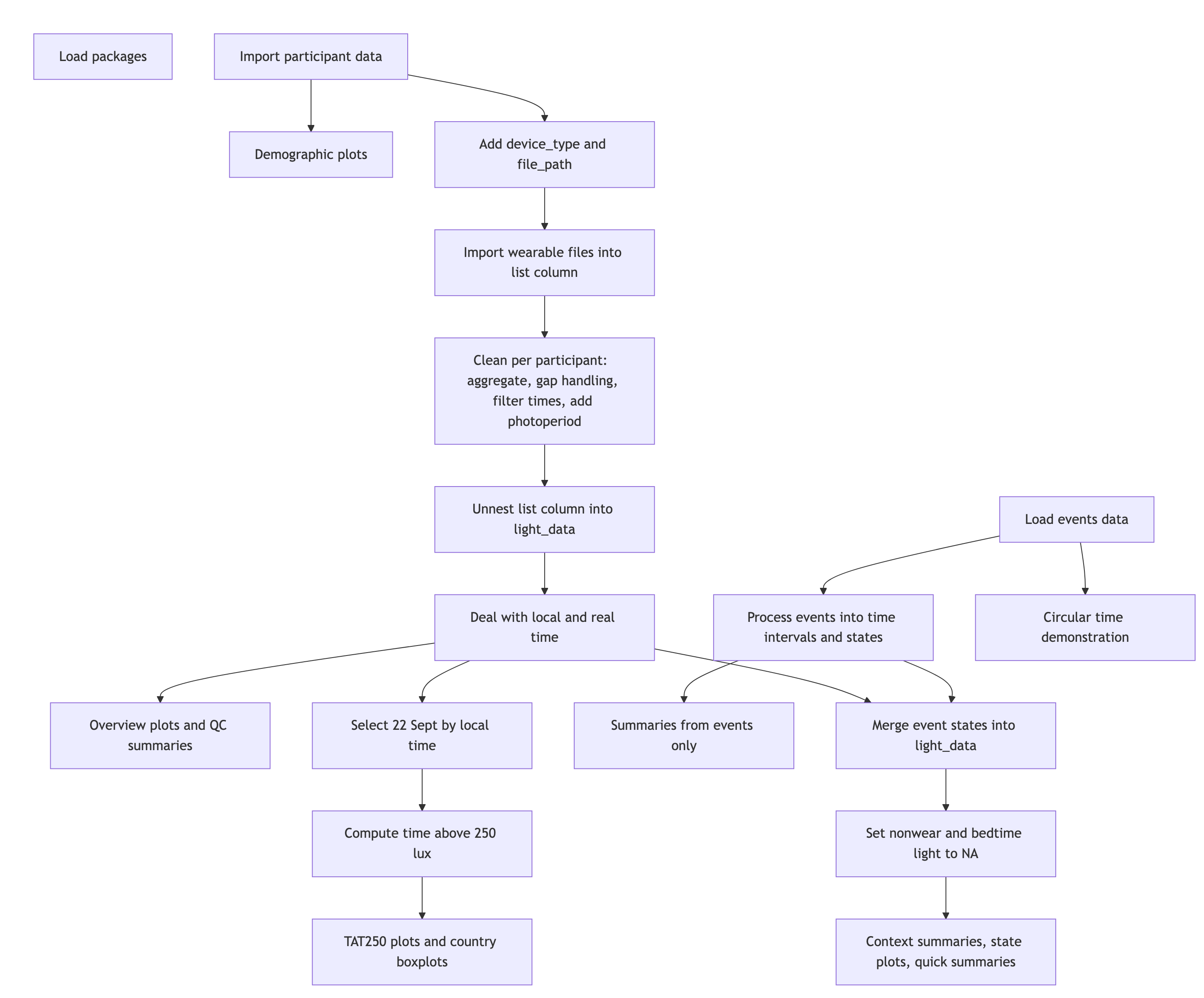

5 Import

Import works differently in this use case, because we import from different time zones and also devices. Would all devices be the same, or would the recordings have all happened in a single time zone, we would simply bulk import with import$device(files, tz)

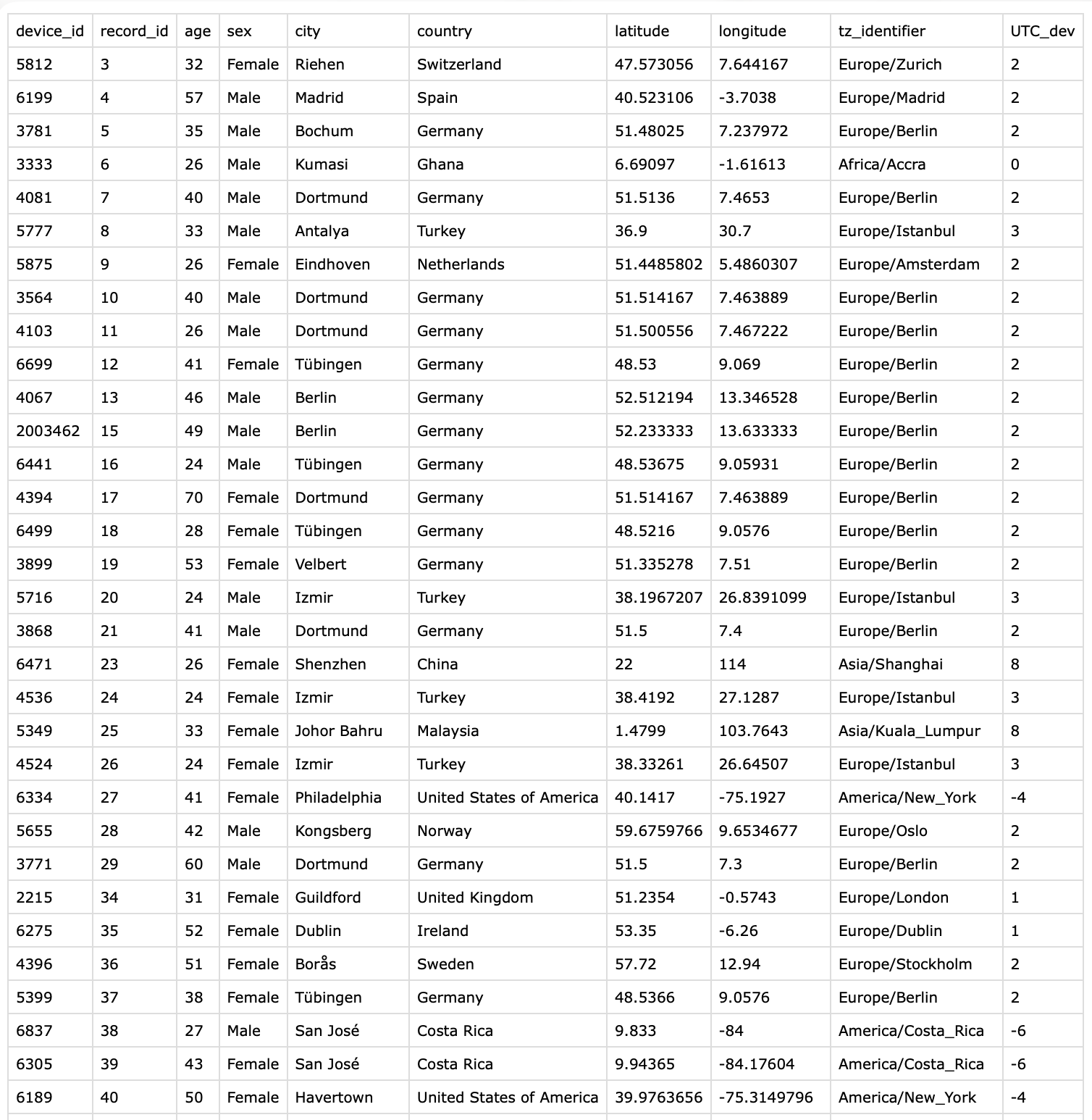

5.1 Participant data

First, we collect a list of available data sets. Data are stored in the folder data/a_day_in_daylight/lightloggers/.

List the filenames from the folder

remove file extenstions (

.txt)

Next we check which devices are declared in the participant metadata collected via a REDCap survey. We want to compare whether the device id’s from the file names match with the survey. Figure 1 shows the structure of the CSV file.

- Collect device id’s from survey

Check whether any entries are duplicated

Check whether all wearable files are represented in the survey

Before we import the wearable data, let’s make a plot of participants’ age(group) and sex.

5.2 Plot demographic data

First, we create a helper for the axis to indicate the sexes.

Then we create the actual plot:

Convert age into age groups (length of five years)

Get the number of participants per age group and sex

Replicate each row n times

Change sign for males’ n

5.3 Import wearable data

Next, we import the light data. We do this inside participant_data. If you are not used to list columns inside dataframes, do not worry - we will take this one step at a time.

There are two devices in use: ActLumus and ActTrust. We need to import them separately, as they are using different file formats and thus import functions. In our case, device_id with four numbers indicates an ActLumus device, whereas seven numbers indicates an ActTrust. We add a column to the data indicating the Type of device in use. We also make sure that the spelling equals the supported_devices() list from LightLogR. Then we construct filename paths for all files.

- Only select participants which are part of the reduced

livedataset.

With this information we import our datasets into a column called light_data. Because this is going to be a list-column, we use the map family of functions from the {purrr} package, as they output a list for each input. Input, in our case, it the device_type, file_path, and tz_identifier in each row. Because the file names contain nothing but the Id, we don’t have to specify anything to the import function regarding Id, as the filename will be used by default.

For the next code cells we have eased the timelimit restriction that are normally set for webR (30 seconds), as this will take some time.

pmap()takes a list of arguments, provides them row-by-row to a function, and outputs a list of results.Inputs to our import function. In our case, because we are using the

pmap()insidemutate, we can directly reference the dataset variables.

7-12. The function we want to be executed based on the inputs

8-11. LightLogR’s import function. We provide the arguments in the correct spot. Because we do not want to have 47 individual summaries and overview plots, we set the import to silent.

We end with one dataset per row entry. Let us have a look.

What about the import summary? We can still import the data the normal way (at least for one device type) - while they will all share the same time zone, it can still be used to get some initial insights about the data.

Select only participants with the

ActLumusdeviceRemove file that has a differing number of columns from the others. Likely, this is due to a software export setting. Importing this file separately would not be an issue, just the mix is not possible.

Import function with standard settings

we are not interested in the actual data, just the side effect of the import summary.

6 Light data

6.1 Cleaning light data

In this section we will prepare the light data through the following steps:

resampling data to 5 minute intervals

filling in missing data with explicit gaps

removing data that does not fall between

2025-09-21 10:00:00 UTCand2025-09-23 12:00:00 UTC, which contains all times where 22 September occurs somewhere on the planetcreating a

local_timevariable, which forces theUTCtime zone on all time stamps. When we later merge all datasets, we will haveDatetimeto compare based on real-time measurements, andlocal_timeto compare based on time of day.adding photoperiod information to the data. It will use the

local_timevariable as a basis

We do this the same way as we imported individual files above, with the pmap function.

Note: the next code cell will take considerable time

Resample to 5 mins

Fill in explicit gaps

10-12. Only leave a section of data

- Adding a

local_timecolum

14-15. Adding photoperiod information and forcing it to the same time zone as local_time.

6.2 Visualizing light data

Now we can visualize the whole dataset - first by combining all datasets. There are two ways how to get to the complete dataset. First by joining only the wearable datasets:

- The

!!!data$light_datais basically equivalent todata$light_data[[1]], data$light_data[[2]],...

Or, and we use this method here, by unnesting the light_data in the data frame. While it requires a manual regrouping by Id, it has the added benefit, that all the participant data is kept with the wearable data.

Note that we are working with two different devices, which export different variables, and also have different measurement qualities. In our specific case, both output a LIGHT variable that denotes photopic illuminance. We thus will use this variable to analyse light in this use case.

In a really study, however, mixing devices would have to be a far more deliberate step, and include some custom calibration.

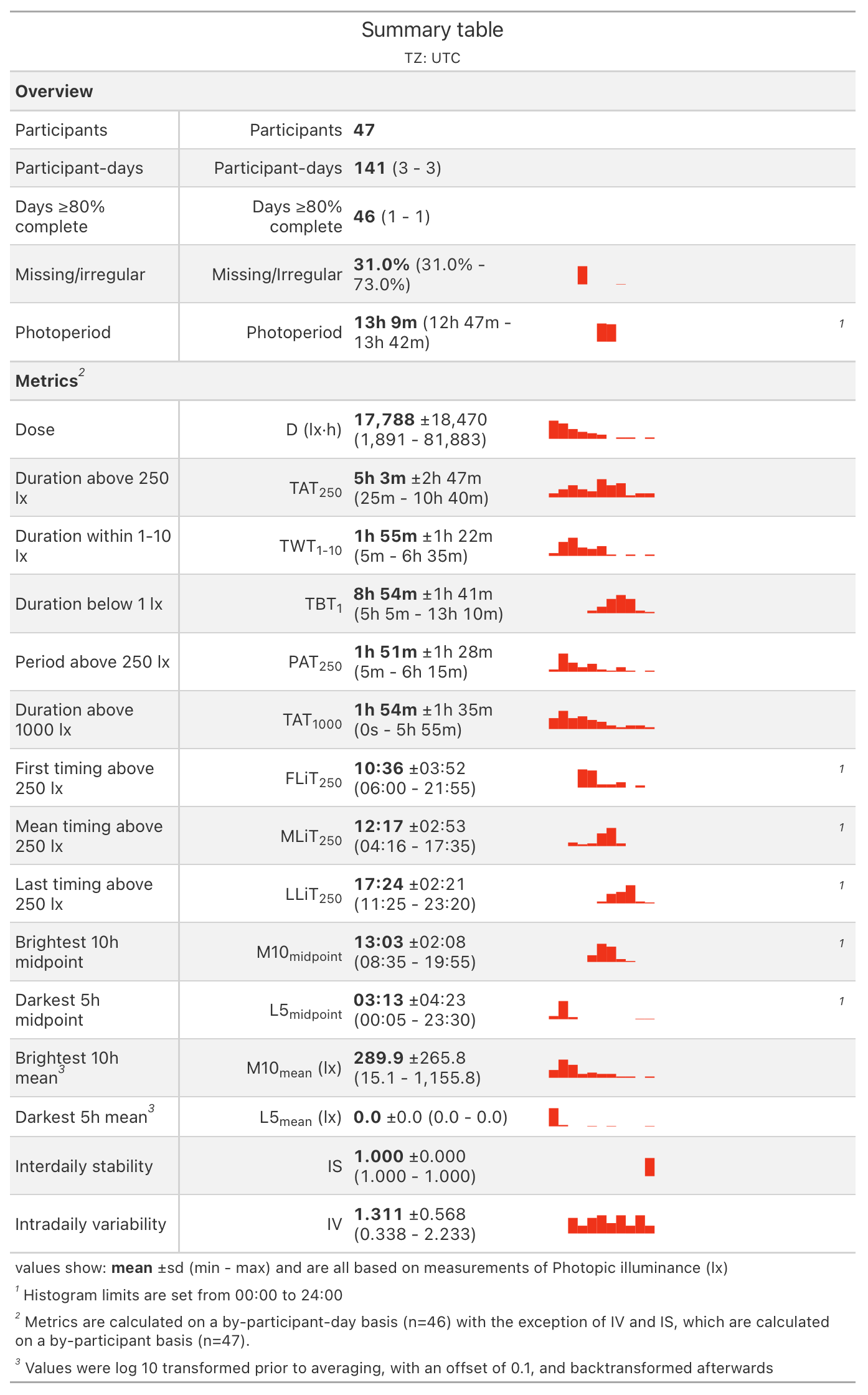

Here are some overviews of the data. With gg_overview():

Overview based on

local_timeOverview based on

real_time(Datetime)

With summary_overview():

And with summary_table()

What are the timezones of our two datetime columns now? Let´s find out

Why is that? local_time can be expected, we set it ourselves above. But why is Datetime now converted to Europe/Zurich. Looking at the first row of the participant data, we see that this is the time zone of the first participant:

When merging multiple time zones, the first time zone will be the one all others are converted to. It helps to remember that the underlying data does not change! Time-zone settings merely change the representation of the time points, not their position in time. The same way that a bar of length 254 mm can be expressed as 10 inches, without it changing the length of the bar. But because the first time zone of the participant list is very arbitrary, we will convert it to UTC as well. Instead of force_tz(), which changes the underlying time point, we use with_tz(), which simply changes the representation. Note that this change is merely cosmetic, i.e., it influences what you see when looking at the data in R. All calculations with that variable would be the same either way.

Then we create border points for the period of interest - start and end points in real time (rt), and in local time (lt), respectively.

Then we plot all the datasets. The resulting figure below shows how they relate in real time.

The next figure shows how they relate in local time, and also include a photoperiod indicator at the bottom.

Replacing the default

MEDIwith ourLIGHTvariable that is available across all device types.Setting the

x.axisto thelocal_timeWe also need to provide the deviating

Datetime.colnamefor the photoperiods, otherwise the calculation of the averageduskanddawnby date will be erroneous.

We can further create a small function that takes an indice and provide the realtime and localtime display of the dataset.

sample_groups()is a convenient way to select groups

7 Time above threshold

In this section we calculate the time above threshold for the single day of 22 September 2025, depending on latitude and country. We require the local_time variable for that. Because we unnested the data into the participant data, that information is available to us.

3-5. We reduce the length of the dataset

7-9. We calculate time above 250 lx

11-13. Extracting coordinates and country

- Calculating how often a country is represented

We plot this information with a custom function, which lets us quickly exchange latitude and longitude.

Ordering the output by their time above 250lx

style_time()is aLightLogRconvenience function that produces nice time labels

- Making the plot interactive

Next we display the metric by country. Because the individual variance of these data is very high, we also choose to add information about the number of individuals within a country.

8 Event data

The last major aspect we will cover in this use case, are the activity logs that participants filled in, whenever their status changed - be it whether they took off their device, changed location, activity, or switched light settings. The activity logs are available as an R object here, this has the benefit that variable labels are retained.

In a regular analysis, we would use the non-wear information at hand before we calculated any metrics as we did in the prio sections. For this online course, however, we set the order of aspects also after didactic aspects. We want to close with this aspect here, as the activity logs are quite complex. Normally, the non-wear information would be added (and those times excluded) much earlier.

We start by loading in the logs and display a small portion:

startdate marks the local time when an activity was logged. As per the instructions, it should be valid until the next activity is logged. This allows us to put start and end timepoints to each row.

The start variable is already presend, but it is a

characterstring and needs to be converted to a datetimeThe duration of a status is the difference of consecutive time points. Because the last log entry does not have a lead, we need to add a missing value at the end.

6-9. For the end, we differentiate between cases where there is no next entry - in those cases, we simply define the length as until the end of data collection. To cover this time span, it is safe to assume a duration of six hours. The end will be automatically capped to the end of the wearable data, when we merge it later on. In cases where there is a next entry, we use the start of the next log entry as an endpoint.

10-15. Creating a general setting that differentiates between the main states

We need to add the

device_idto the event data, the link is therecord_id, which needs to be numeric for line 19All the operations above need to be performed on a by-participant fashion

19-21. Adding device_id. For the merge, it needs to a factor Id, which is the grouping variable in light_data

- Removing all

record_id’s that are not part ofdata

To get a feeling for the event data, lets make some summaries.

So a total of 10 participants collected on average 36 log entries (at minimum 19, at maximum 66)

Then we can summarize the general conditions in the following table. None of the following code cell functions are using LightLogR, but feel free to explore what each one does anyways.

8.1 Combining Events with light data

In this step, we expand the light measurements with the event data.

- To properly add the states information, we need to select the

local_timevariable

Next, we can visualize the activity logs together with the light information. To facilitate this, we again create a helper function. This opens a whole range of options to explore participants and states

8.2 Remove non-wear

As we now have logs of non-wear (both during the day and in sleep), we can set those measurements to NA. Before that, let’s check what the average value is during each state:

Now let’s remove these measurements.

We can check whether we were successful, by summarizing our data depending on type.

This shows us that removing those instances was successful. To close up this use case, we can calculate a few metrics depending on the context with a helper function:

Calculate the duration of every state for each participant

Calculate the average duration per state across participants

7-17. We add the geometric mean to the summary with extract_metric, and supply the original dataset, grouped in the same way as our summary is

12-13. Secondary settings

14-16. The formula for the geometric mean uses log_zero_inflated() and its counterpart exp_zero_inflated() to allow for zero-lx values in the dataset

With this helper we can get quick overviews for many aspects:

9 Circular time

We close this use case off with with a small detour to averaging of times. Many calculations in wearable data analysis involves averaging. This is tricky for variables that are circular in nature, like the time of day. consider the following case:

When we take the average of these two, we get noon on 8 December.

Depending on what the values represent, this is a correct handling. But consider they represent sleep times. In this case the averaging results to not output what we want, especially the sensitivity to the date for the result. We can lose the reliance on the date if we use a function like Datetime2Time() or summarize_numeric()s defaults:

Now we have consistent results - but they are still wrong in the context we are thinking in. We need circular time for this, i.e., where the distance of two timepoints is equal, even across midnight. LightLogR has implemented functions from the circular package to make this process easy. Simply specify a circular handling. After the summary, apply Circular2Time() to backtransform to the common representation.

We can use this approach in our use case. Say we want to know the average Bedtime of people, based on their logs:

Now focus on the difference of whether we work with circular time or not:

10 Conclusion

Congratulations! You have finished this section of the advanced course. If you go back to the homepage, you can select one of the other use cases.

Footnotes

If you want to know more about

webRand theQuarto-liveextension that powers this document, you can visit the documentation page↩︎